On the Origin of Hygiene...

and beyond

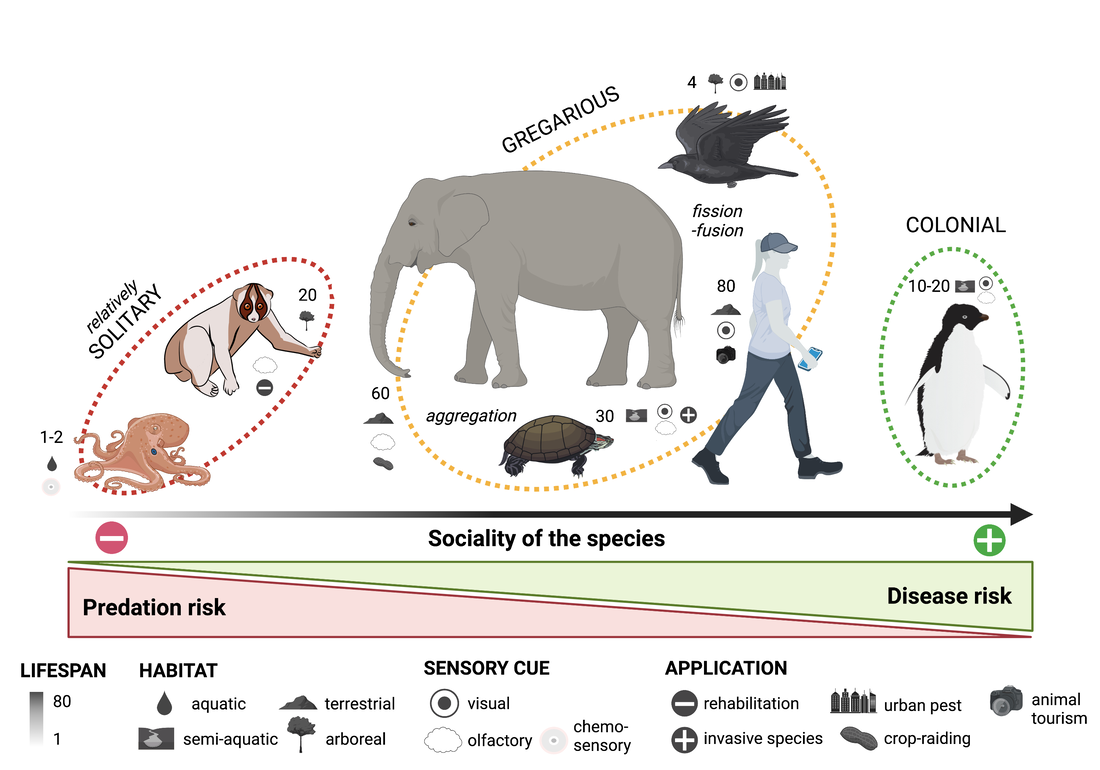

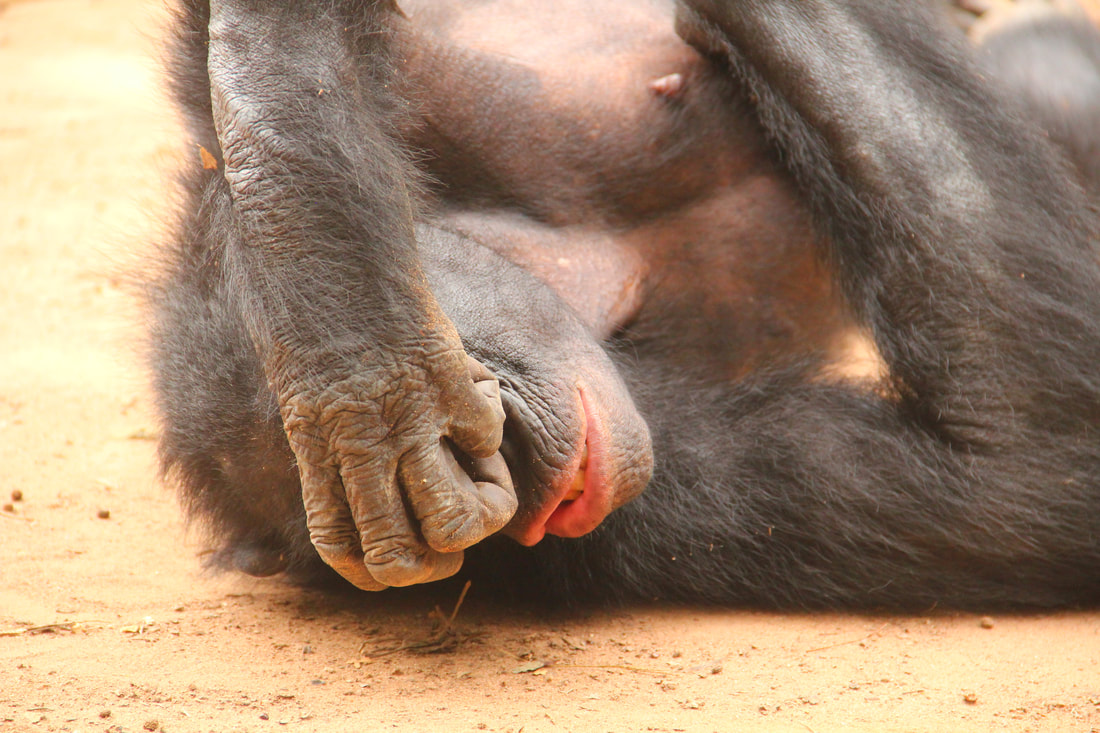

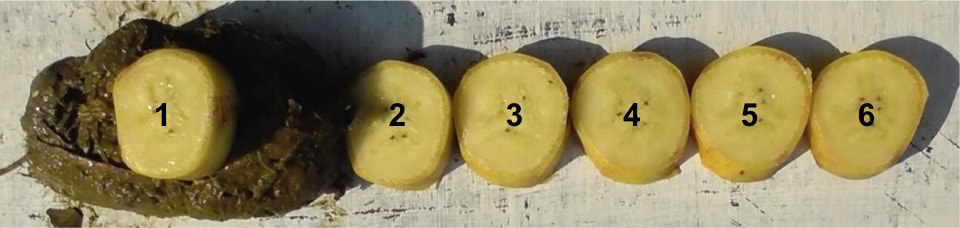

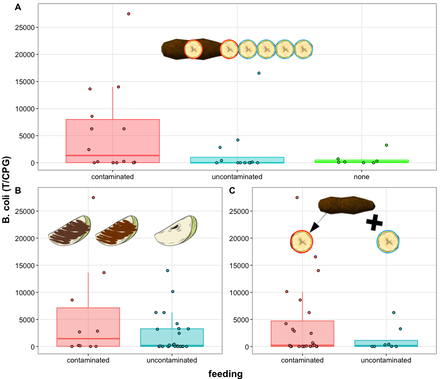

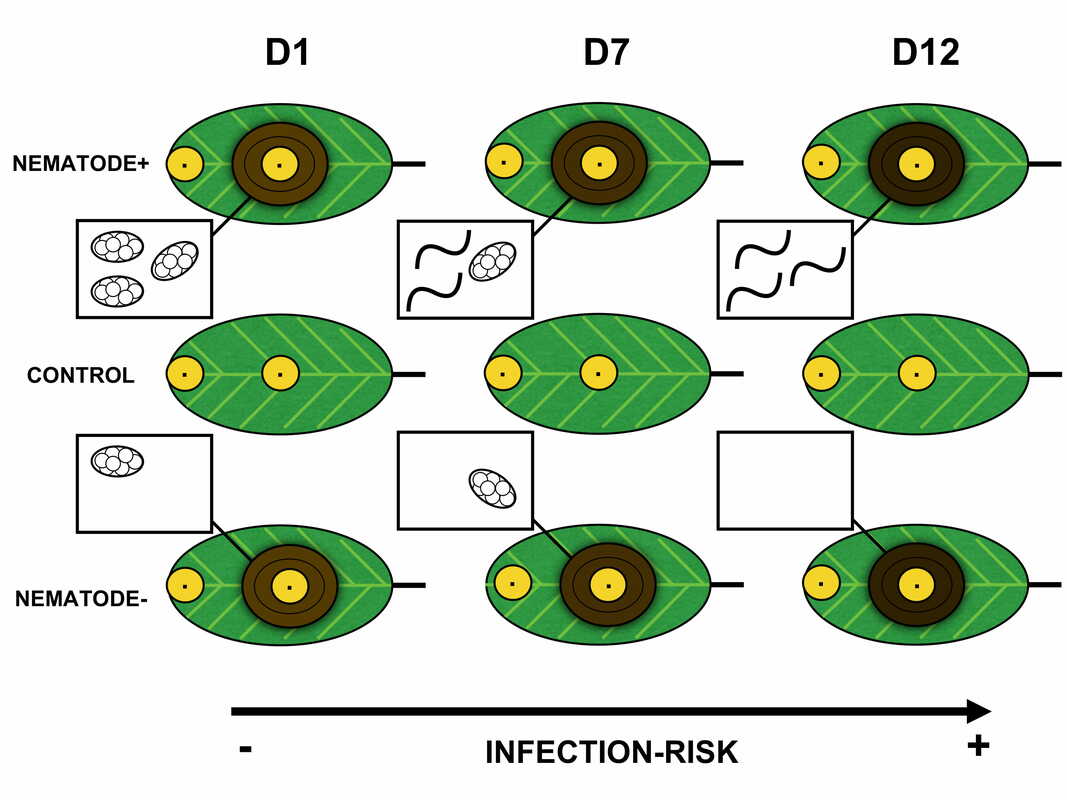

As a cognitive ecologist, I am broadly interested in how animals stay healthy in their natural environment. Which behavioral avoidance strategies do they adopt against pathogens and parasites? In humans, hygiene is supposed to take its roots from the primitive emotion of disgust. By being disgusted, people stay away from parasites and infection. Then, can the mechanism of disgust also be a driver of parasite avoidance behavior in our closest phylogenetic relatives? These were the questions my PhD addressed. Now, as a postdoctoral researcher, I aim to explore the cognitive and physiological responses to disgust elicitors as well as looking at potential applications of disgust in the field of Conservation. Understanding how other animals react to potential sources of infection can illuminate the drivers of infectious disease transmission and its potential behavioral mitigation, as well as the evolutionary history of infection-avoidance strategies in humans.